Describing Biodiversity

The first step in wisdom is to know the things themselves; this notion consists in having the true idea of the object; objects are distinguished and known by their methodical classification and appropriate naming; therefore Classification and Naming will be the foundation of our Science. ~ Linnaeus (1735), quoted in Stevens (1994:201), quoted in Winston (1999:3)1

Why is biodiversity important?

Biodiversity is important to humans because of their major roles in the ecosystem function. The benefits that we avail from ecosystem functions are known as ecosystem services. We rely on ecosystem services for our food, fresh water, shelter, health, safety, among others. Additionally, our global economy is dependent on the state of our biodiversity and environment. We have witnessed time and time again, the direct negative impacts to us, humans, whenever biodiversity is over-exploited. What happens? An imbalance between man and nature, with man causing excessive destruction of nature, the result of natural disasters, drought, diseases, unnatural infestation of bugs and pests, and many more. By doing all these, we are reducing our very own protection from harmful elements and source of provision for our needs to live on earth. It is good though that our awareness of such facts has increased awhile as we sought solutions for the problems that confront us right now. We have learned that saving biodiversity is a pressing issue that involves not only a few groups of individuals but, everyone who inhabits the planet. To that event, the task of understanding life around us by describing biodiversity comes first, before we can protect them.

Describing biodiversity: An introduction

To manage and protect our biodiversity, we need to have an idea of what they are and how many of them are there. We need to be able to describe them by giving them names and putting them in categories of similar groups. Then we need to have an estimate of how much they are that exist, and the locations they are found. It sounds simple, doesn’t it? However, in 1777, Carl Linnaeus sighed in desperation in his deathbed, “Am I to work myself to death, am I never to see or taste the world? What do I gain by it?” At that time, he was a single person working on classifying every plant and animal species of the world. In fact, he published in 1735 the first edition of Systema Naturae, and later on compiled 12 more editions before he died (Lindroth 1983:31 in Winston 1999:31). This enormous task of “describing biodiversity” was eventually passed on to his students and other explorers who have gone to the vastness of the planet.

Thanks to the great work of the Father of Systematics (Linnaeus) who started what is now called taxonomy, the science of naming, describing and classifying organims2. By recognizing similar characters of living creatures, we can identify them according to their lowest taxon (unit) available. We call it species. However, in many cases now, through our advancing knowledge and technology of species collections and recognition such as the use of AUVs, ROVs, high-tech electronic microscope and DNA sequencing, species identification has advanced significantly recognizing taxa below species level and finding representatives in many unexplored depths of the earth.

It used to be that the number of species known to science was 1.75 million. The truth is, it has now increased tremendously as we discover new habitats and ecosystems. Expeditions to unknown regions of the planet have allowed our scientists to be awed not only by the vastness of life forms but also their intriguing diversity. There is simply much to be explored and described. Millions of species await the attention of taxonomists, so they can be described and given names. However, there have been concerns that they may first be extinct before they are discovered. 1,3b

According to the current census of life done in 2011, the latest estimate of species on earth is 8.7 million. Of these, 6.5 million species are terrestrial while 2.2 are aquatic. The census further showed that 86% of the 6.5 million land species and, 91% of the 2.2 million sea species are yet to be explored, described and recorded. That’s a lot of species to work on.

The scientists who came up with this estimate said that they used an ingenious, and approved analytical method that significantly narrowed down the range of earlier estimates. They worked on the assumption that there is a consistent pattern in the taxonomic classification of species into higher groups (i.e., from genus, to family, to phylum, to kingdom). And therefore, predictions can be done on the total number of species given a taxonomic group. Wide projections count all living species to be between 3 million and 100 million.3a,3b

Note that the estimates of undescribed species keep on growing when the insect group such as mites and beetles, and unsegmented worms called nematodes, are taken into account. Their small size and preference for specific hosts or habitats, adds more challenge for them to be found.

Interestingly, on May of this year 2016, new estimates have been predicted by researchers based on combining universal dominance scaling law and biodiversity models. The prediction was applied on the abundance of dominant ocean bacteria. Using these data, they came up with the result that the Earth is a home to 1 trillion (1012) microbial species.

Microbial biodiversity seems to be far more abundant than what we have thought. The prediction process that the researchers uncovered may have potential in predictions for biodiversity richness, commonness and rarity in all scales of abundance. They encourage further investigation of the process. However, the possibility of applying the same techniques in species estimates could be useful.5

The Need to Describe More Species

We need to have our species descriptions and counts organized to be able to come up with effective management plans on biodiversity. This knowledge will equip us when setting conservation priorities, budget, efforts, manpower and other aspects of decisions that we need to make.

The Catalogue of Life (CoL) is a global listing of all species of all life groups (taxa). It gives us a picture of how many species are known for each category. In the figure below, we can see the distribution by the number of species from each known kingdom. CoL uses 8-kingdom classification. Its data come from the listings of specialists taxonomists on particular groups of organisms.

This benefits all of us as we gain sound information about all the species around the world. Currently, CoL catalogues 1.68 million species and the list grows each year as more contributors participate.

Examples of biodiversity descriptions

Describing biodiversity requires describing life forms to the species level. Whether it’s an animal, plant, fungi or bacteria, species descriptions are necessary to fully characterize the array of biological information of a species. Some of which may include morphological uniqueness, habitat requirements, distribution and DNA-based characters. Each group in the higher taxonomic levels will have different methods on how they’re described. What could be true for fishes, will not be true for marine mammals and so with spiders. For that, taxonomists are highly specialists. Depending on how much diverse a particular group is, taxonomists may specialize on describing species from certain families of an order of the Animal kingdom, for example. The task of species description, especially for new species requires true dedication, diligence and cognitive abilities.

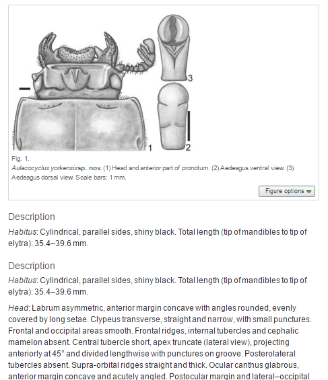

Here’s an example of a scarab beetle’s new species description found in Adelaide, Australia.

The science and art of Binomial Nomenclature

We have mentioned that living organisms are divided into groups, called taxa. Members of the group are classified according to rank or taxonomic hierarchy, where we recognized species being the typical lowest or standard level. Below the species level are more specialized units called the subspecies, populations and individuals. Above the species level, are the higher taxa with more generalized common characters. Species that share the same characters are grouped into genus. Genera that share the same characters are grouped into family, families into orders, orders into classes, classes into phyla, phyla into kingdom. Each group has a name assigned to it, such as the class of fishes is called Pisces, the order of marine worms is called Polychaeta. This part of taxonomy involving names is called nomenclature. There’s a big committee of biologists whose task is to assign and reassign scientific names as they follow sets of rules known as Codes of Nomenclature.

Linnaeus first used the binomial nomenclature system in 1753 to clearly refer to specific plants and, in 1758 to animals.1 We have adopted the same system today to address names of specific organisms. We call it scientific name, composed of a genus name and a species name, which both use Latin forms. Notable examples of scientific names that were named after famous people are: the Brad Pitt wasp from South Africa known as Conobregma bradpitti, the Angelina Jolie trapdoor spider from Monterey County, California called Aptostichus angelinajolieae and the “Green-day” plant from Ecuador (named after the American punk rock band Green Day, “dies-viridis” in Latin) Macrocarpaea dies-viridis.

What is a biodiversity hotspot?

It is a biogeographic region anywhere around the world that has a high number of endemic species and is also highly at risk because of human-related destructive activities. Endemic species are living organisms that are only found in a specific location such as an island, a country or a habitat, and nowhere else on the planet. There are now 36 biodiversity hotspots that are identified for conservation priorities. Conservation leaders believe that by succeeding in conservation efforts in these 36 regions, we can make a significant impact in conserving biodiversity in a global scale. This is a more effective strategy to save biodiversity from extinction, especially at this time when many species have been unbelievably vanishing at the fastest rate recorded in history.

Importance of biodiversity descriptions in conservation

Studies have shown how the rising temperature changes almost everything around us. Not only the timing and extremities of weather, but also the structure of our ecological systems. With this change happening, we need to be quick in gathering the basic information, such as what species we have at specific timelines and geographical range. Through a baseline information, we are prepared to measure the changes that may happen in the future. Also, our biodiversity research can progress from these baseline information. Research discoveries can advance as each species are described and catalogued. We aren’t left clueless and guessing with what’s happening around us. Instead, we have validated information that will guide us in making wise decisions concerning biodiversity and our future. Describing biodiversity is critical in working on conservation programs and policies that will effectively protect our environment.

References:

1 Winston JE 1999. Describing Species: Practical Taxonomic Procedure for Biologists. New York: Columbia University Press, 518pp.

2 Actually, historically speaking, the first taxonomist was Adam. Read Genesis 2:20.

3a How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?

3b 8.7 Million Species on Earth

Supplementary Resources:

1 Map download of CoML “Ocea Life: Diversity, Distribution, Abundance” >

2 Online tool to create your own Tree of Life

Title Image Credit:

“12 NaGISA_Various_polychae-1300dpi” by Census of Marine Life E&O , used under CC BY | Desaturated from original